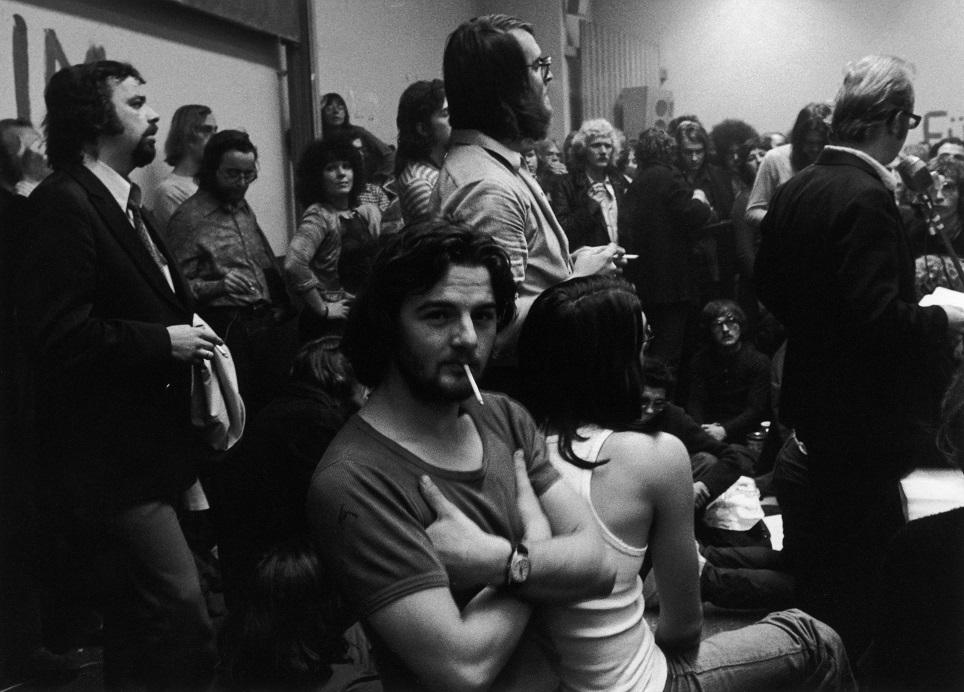

The young musician and musicologist Khrystyna Petrynka fled from Ukraine and is now in Berlin, where, thanks to the scholarship program of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (SPK), she is once again devoting herself to the bandura.

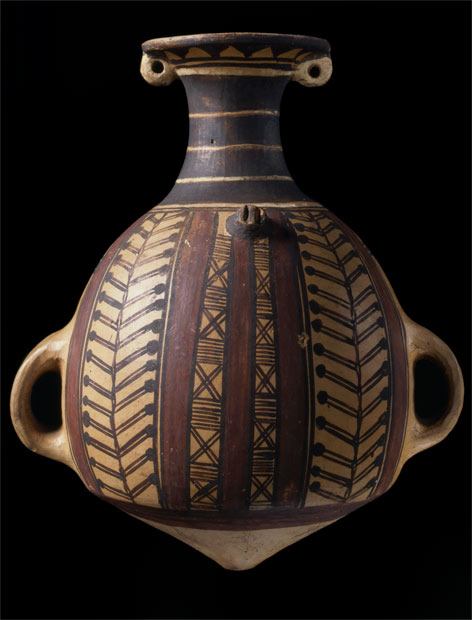

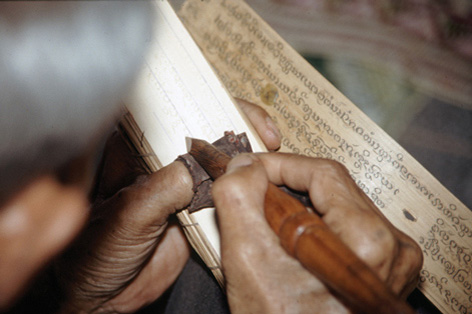

After she has told her story – of her love for music, her life in Ukraine and her escape to Germany – 22-year-old Khrystyna Petrynka reaches for her instrument and starts to play: a piece by Handel first, then a little jazz, and lastly, a song by Marina Krut, the popular Ukrainian singer. Petrynka is a passionate player of the bandura, the Ukrainian string instrument that combines features of the lute and zither. She wants to show just how much is possible with this instrument, and that it's not to be dismissed as old-fashioned. Above all, though, it represents her country: "The bandura is the voice of Ukraine," she says. Especially now, during the war.

She recalls developing an interest in the bandura early on, inspired by a music teacher at school. "Bandura is my life, that was clear to me even back then," she says. Later, at the university in Lviv, Petrynka even wrote her master's thesis on the bandura, which was not at all a typical path to follow, she says. But just as she was about to begin work on her dissertation, Putin's troops attacked her country. Shortly afterward, Petrynka fled to relatives in Frankfurt. In a fortunate turn of events, Rebecca Wolf, the director of the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung (State Institute for Music Research), learned of her interrupted studies and brought her to Berlin via the scholarship program of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation).

Meanwhile, the SPK has expanded its scholarship program and created twenty additional spots throughout its member institutions for Ukrainian scholars fleeing the war. The scholarships are initially provided for up to three months and offer up to 1,200 euros per month.

The application process and requirements have been simplified, but it is still important that the research topics chosen by the applicants have some relation to the SPK collections in Berlin. Inquiries and expressions of interest have been coming in for many weeks now, and the first scholarship holders, including Khrystyna Petrynka, have already arrived and settled into life in Berlin. Every day, she goes to the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung (State Institute for Music Research) and to the Staatsbibliothek (Berlin State Library) and continues her self-directed study of the bandura. She is delighted by the Institut für Musikforschung with its many resources and its unique combination of music history and instrument research. Together with the conservator for plucked string instruments, she has already inspected the precious bandura in the storeroom of the Musikinstrumenten-Museum (Museum of Musical Instruments).

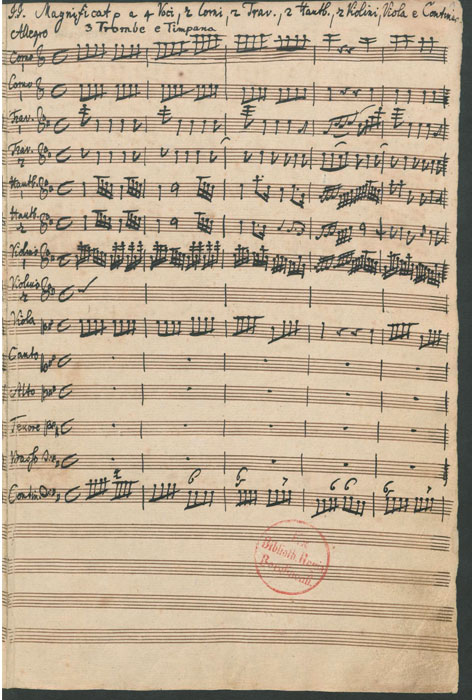

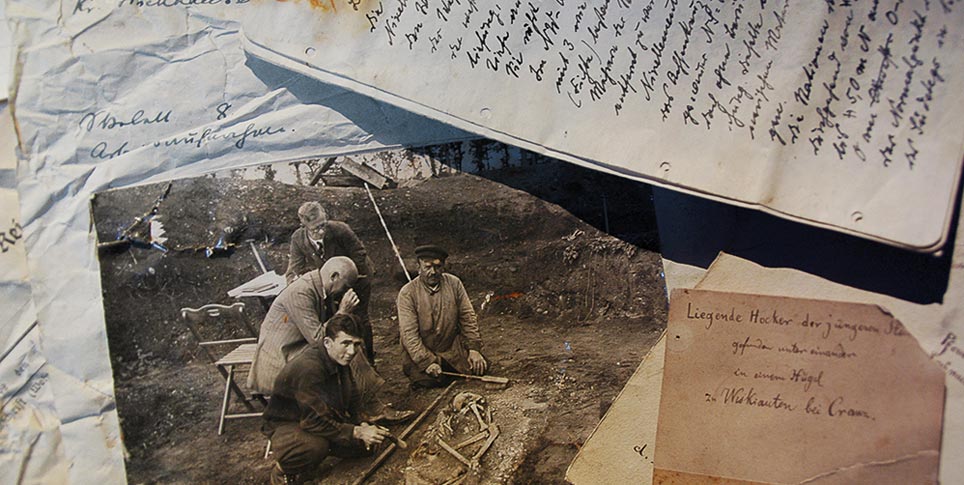

Khrystyna Petrynka is a true specialist, an expert with an impressive command of theory and practice who can combine them to create something new. Not only is she an ardent player of the instrument, she can deliver a proper lecture on it, too, and with just as much enthusiasm. She starts by explaining the instruments' parts: the fingerboard, the sound box, the strings. Then she reaches for her bag and takes out an essay that she wrote on the era of the free warriors, the Cossacks, and talks about a time when the bandura players are said to have made their instruments themselves and played them without accompaniment, like the troubadours in France. Ultimately, in the twentieth century, city people began to take an interest in the bandura too, she explains. There was experimentation with playing techniques, and bandura ensembles were formed. Around this time, scholarly interest in the instrument also emerged when Gnat Khotkevych, a charismatic player and author, published textbooks on it. And regardless of whether the young Ukrainian is describing the popular Chernihiv bandura, the Lviv bandura or the once widespread Kharkiv bandura, it is always made clear that these are expressions of Ukrainian patriotism, that the bandura is a symbol of the struggle for freedom.

Grant Program of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz

The Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz has established its own Grant Program. Each year, it welcomes approximately thirty visiting scholars from across the world and makes it possible for them to pursue their research at one of the Foundation’s institutions.

The SPK has expanded its fellowship program by 20 additional places for refugee Ukrainian (and persecuted Russian/Belarusian) scholars and librarians. The project applied for should have a meaningful connection to the collections or research focus of the respective SPK institution.

For Petrynka, after all, it is obvious that the bandura is not just an old instrument with a great tradition; it is something akin to the Ukrainian national instrument. It contributes to a sense of national identity, all the more so in these days of war. To illustrate this point, Petrynka points to videos that have been published on Instagram and YouTube. In one of them, we see a musician amidst a field of rubble, singing and playing the bandura in front of a destroyed tank. "The bandura players are really our heroes; they sing about our inner strength," Petrynka says. In recent years, more and more people have taken up the instrument, young people in particular. The repertoire has expanded, and stereotypes have been jettisoned.

These days, the bandura isn't about folk music; it's not something old-fashioned. Bandura players are performing rock, pop, jazz and electro. It's an expression of a fresh national spirit, albeit one deeply rooted in Ukrainian history. "In 2010, in a talent show, we saw how modern it can be to play the bandura," says Petrynka. She sings the praises of famous bandura players and talks about stars, festivals, competitions and concerts, about "Wild West Jazz" (the first major music video with a bandura, which appeared in 2011) and about the music project "Sounds of Chernobyl," which also integrated the bandura – all very cool, very contemporary.

And when the SPK scholarship is over, what's next? First, the young musician would like to remain in Berlin until the war is over, she says. She has plans to write articles about the bandura for professional journals; she intends to give a presentation at the SIM Research Colloquium; and on June 12, she wants to perform at a workshop as part of an open house day at the Berliner Philharmonie and the Musikinstrumenten-Museum. And she will continue to follow her chosen path and develop her very own bandura interpretation. Because Khrystyna Petrynka has a message, and it makes her eyes light up when she shares it: "Ukrainian culture is fantastic."