The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library) has acquired an exchange of letters between a Prussian writer, Karl August Varnhagen von Ense, and a British noblewoman, Charlotte Williams-Wynn. Everardus Overgaauw, the head of the Manuscript Department of the Staatsbibliothek, on the unusual background to the acquisition.

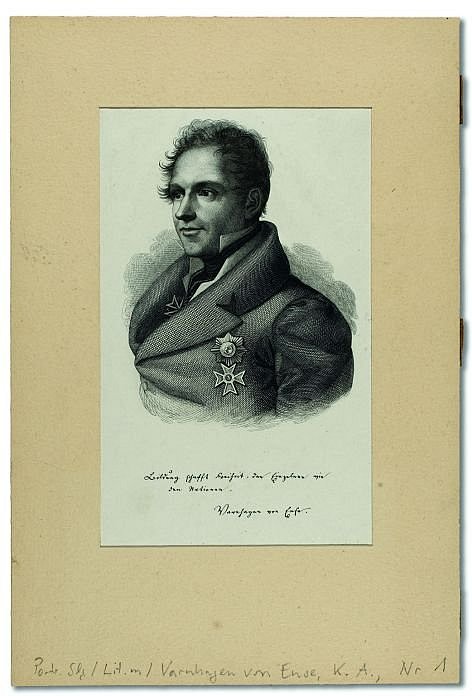

Karl August Varnhagen von Ense (1785–1858) embodies the rise of Prussia and Berlin during the first half of the nineteenth century like few other figures of his time. Born in Düsseldorf and trained as a doctor in Berlin, Halle and Tübingen, he carved out a successful career as an officer in the service of Austria – and later of Russia – in the wars of liberation against Napoleon. After the war, in 1814, he became a Prussian diplomat. After retiring from the civil service in 1819, he lived in Berlin as a citizen without an official position. He published several books, mostly biographies, as well as numerous essays and short articles commenting on the political and cultural events of his time. In 1814 he had married the esteemed letter writer and salon hostess Rahel Lewin. Their home became a center of social life for a cultured circle in the Prussian capital. Thanks to his wealth, acquired during the Napoleonic Wars, and her inheritance, the couple could afford to maintain an upper-class lifestyle. Karl August loved Rahel very much, and among their acquaintances in Berlin, their marriage was considered exemplary. He was deeply grieved when she died in 1833 at the age of only 61.

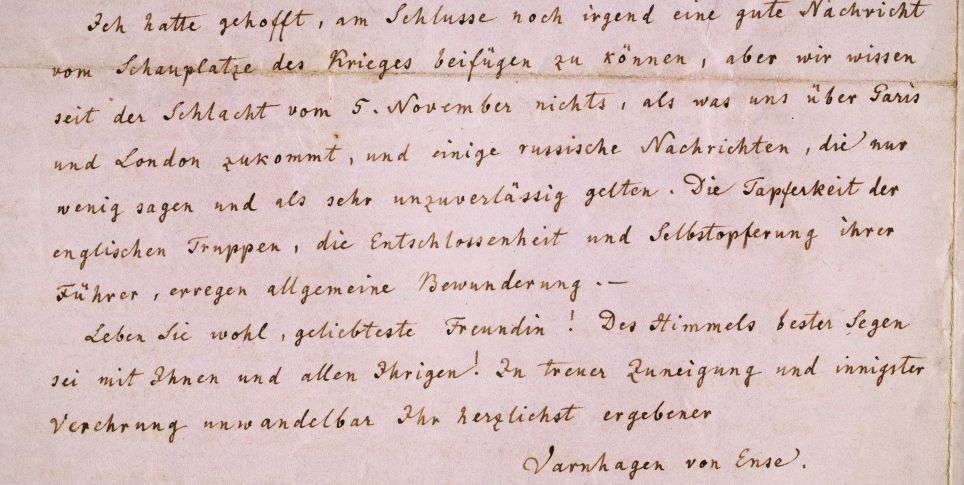

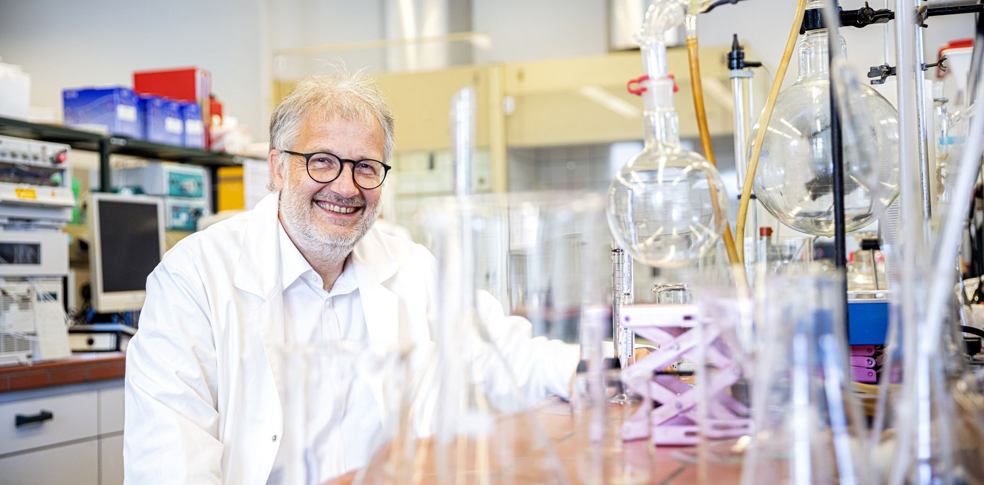

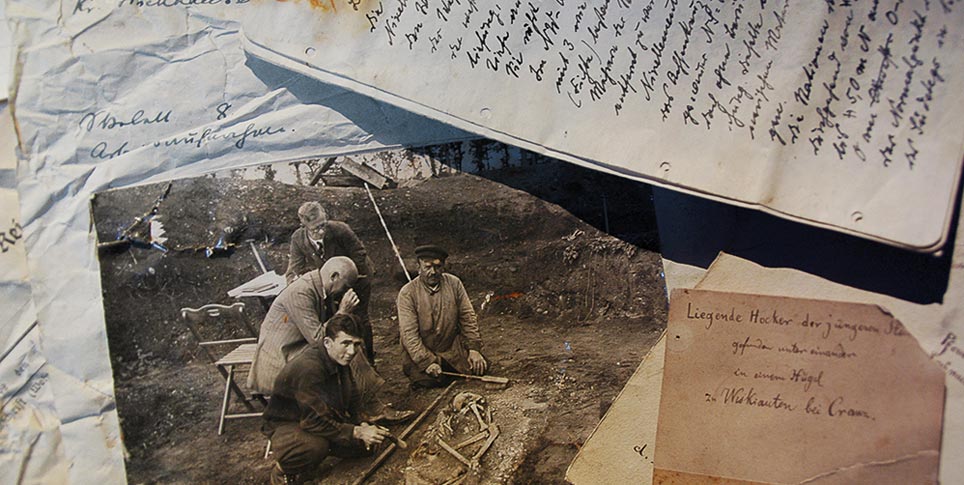

Varnhagen-Letters, SBB-PK, Handschriftenabteilung

Not only did Varnhagen conduct extensive correspondence, he also collected documents (mostly letters) written by his contemporaries. His important autograph collection (more than 200,000 documents) passed to the Prussian Royal Library in 1881 along with his own diaries and books. This legacy of manuscripts was moved out of Berlin to relative safety in Silesia during the Second World War, but afterwards it was not returned to Berlin. It ended up in the Biblioteka Jagiellońska in Krakow, where it remained as the “Berlinka” archive. Only a fraction of the Varnhagen legacy is in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin today; this includes the portrait collection and a small part of the autograph collection. Several dozen letters from Varnhagen can be found in the estates of his correspondents, such as Adelbert von Chamisso and Leopold von Ranke. The library acquired further Varnhagen letters from an antiquarian bookshop.

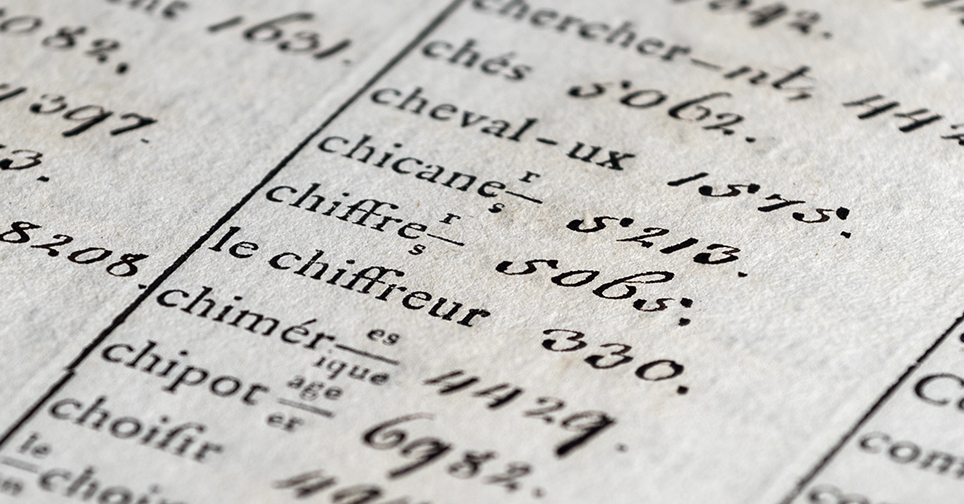

Early in November 2019, I was informed by the London auction house Bonhams that 350 letters written by Varnhagen to Charlotte Williams-Wynn were to be auctioned on the 4th of December. Would the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin be interested in purchasing these letters? Yes, it was. But who was Charlotte Williams-Wynn? And why is she barely mentioned in biographies of Varnhagen? Charlotte Williams-Wynn (1807–69) was a daughter of Charles Williams-Wynn (1775–1850), a Welsh aristocrat and politician . She met Varnhagen for the first time in 1836, at the age of 19, when she and her father were traveling by steamer from Rotterdam to Düsseldorf. They made each other's acquaintance on the Dutch section of the journey up the River Rhine; Varnhagen disembarked in Düsseldorf and met the two of them again in Koblenz. They got to know each other better in Ems in August 1836, partly through language lessons, and it was Charlotte who began the correspondence there before continuing on her way to Wiesbaden.

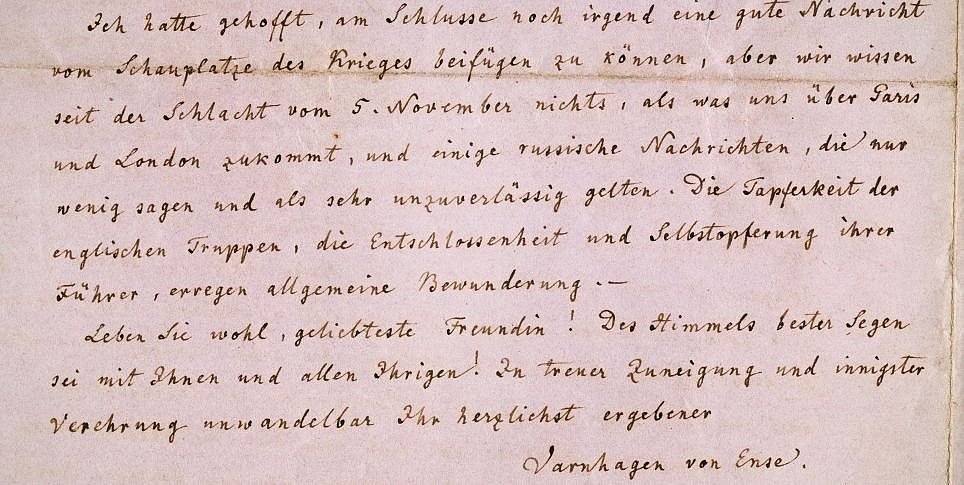

Varnhagen must have been quite impressed by his encounter with Charlotte, and his reply to Charlotte's first letter opened the way for a lively meeting of minds. In his letters, Varnhagen expresses affection for his correspondent, and later also feelings of love. Besides that, he provides Charlotte with a wealth of information about political, social, and cultural life in the Prussian capital, including details of new books, concerts, exhibitions, state visits, and other political events. The long excerpts from Varnhagen's letters that are published in Bonhams auction catalog clearly show their importance as historical documents. The letters also show that Varnhagen did really fall in love with Charlotte. After their first meeting in Wiesbaden, they met in person a few more times. In 1839, Varnhagen even asked Charlotte to become his wife, but she turned him down, although the affectionate and profound relationship in their letters evidently did not suffer as a result.

In addition to Bonhams auction house, the English owner of Varnhagen's letters contacted me to ask whether the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin would be interested in acquiring them. This was Charles Harvey, a descendant of the Williams-Wynn family, who had taken the letters to Bonhams. I immediately replied in the affirmative, but added that my wish could not be fulfilled without the requisite funds.

On the 29th of November 2019, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung published an excellent article about Varnhagen and his richly informative letters to Charlotte, concluding that the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin really ought to buy them. This article, including that final sentence, had been read with interest by a Berlin businessman, Hans-Jürgen Thiedig. He then contacted me with an offer to support the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin in its efforts to acquire the Varnhagen letters. Speaking to me on the telephone, Mr. Thiedig spontaneously agreed to donate a five-figure sum. I accepted this wonderful offer with heartfelt thanks on behalf of the library. In the week before that, I had contacted the Bernd H. Breslauer Foundation and had asked whether the foundation would be able to help the library. Felix de Marez Oyens, the president of the Breslauer Foundation, also promised a five-digit sum, on top of which the Staatsbibliothek earmarked a comparable amount from its budget for acquisitions. Now I was ready to take part in the bidding process by phone on the 4th of December 2020. One by one, the other bidders dropped out as the price rose. I was delighted when the gavel fell and it was confirmed that I had acquired Varnhagen's letters for the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. A little later, a brief e-mail from their previous owner, Charles Harvey, appeared on my computer: "Dear Professor Overgaauw: Was it you?" My answer was even shorter.

When the Varnhagen letters arrived at the library in mid-January 2020, the relevance of the new acquisition was confirmed in my mind after reading only a few dozen of them. Varnhagen had access to what we nowadays call insider knowledge. Few others were so well networked within the political and cultural elite of his time. His knowledge of matters in Berlin is apparent not only in his copious diaries, but also in his letters to Charlotte. The quality of these letters also aroused the enthusiasm of Peter Sprengel, professor emeritus of German studies at the Freie Universität Berlin. He is now preparing a monograph on Karl August and Charlotte, in which many of the former's letters are to be published for the first time.

Sometimes a lovely story has a sad postscript, but this one doesn't.

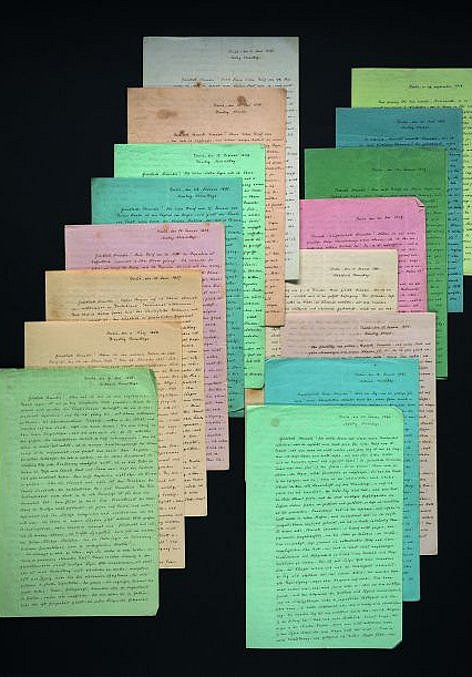

On the 10th of February 2020, Charles Harvey contacted me again, this time to tell me that he had found a box in the attic of his country house in South Wales that contained an envelope with numerous letters. They were the letters from Charlotte Williams-Wynn to Varnhagen, which had been thought lost – the letters corresponding to those that the Staatsbibliothek had recently purchased in London. After Mr. Harvey had opened the envelope and sorted its contents, it turned out that 133 letters from Charlotte to Varnhagen from the period 1836–58 had survived. Their correspondence is most frequent in the years between 1842 and 1846. The letters from the period 1848–50 are evidently missing.

The list of places where Charlotte's letters were written reads like a list of holiday spots favored by Europe's upper classes in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, apart from Charlotte's residences in London and the countryside: Wiesbaden, Nice, Paris, Heidelberg, Basel, Lucerne, Bath, Rome, and Bad Kreuznach. Varnhagen's long friendship with his 'pen pal' Charlotte lasted up to his death in 1858. She spent most of the years that followed – the last ten years of her life – in London and the south of France. She died unmarried in 1869.

Charlotte Williams-Wynn was highly educated, as we can see from her letters, and they also show that she was not at all averse to Varnhagen. She reciprocates his affection and she tells him about things that mean a lot to her, and what is happening to her relatives, and her views on political and religious matters. So why did she turn down Varnhagen's request to be his wife? For that, a closer reading of the letters will be needed. Was religion the problem? Charlotte was a devout member of the Church of England while Varnhagen was a non-practicing Catholic. Was it the difference between their social classes, which in those days was very important? Charlotte was the daughter of a baron, no less, while Varnhagen, despite the suffix 'von Ense' in his name, had to explain his status as a nobleman. And while Charlotte's family was wealthy, Varnhagen could at best be described as well off.

Varnhagen's letters to Charlotte remained in the possession of her descendants over the generations. Charlotte's letters to Varnhagen must have been handed over by his heirs either to Charlotte or to her heirs. That would explain why Charles Harvey inherited both halves of the correspondence. The number of Charlotte's letters to Varnhagen (133) is considerably fewer than the number of Varnhagen's letters to Charlotte (350). So far, there is no satisfactory explanation for this difference. Did Varnhagen write more often than his pen pal? Did Charlotte's heirs dispose of letters that they deemed unacceptable? Did Varnhagen's heirs not return all of her letters? The last explanation, at least, seems to be true: the Berlin archive in Krakow contains letters from Charlotte to Varnhagen from the period 1836–39, as well as some copies of letters from Varnhagen to Charlotte. The fact that Charlotte probably never visited her correspondent in Berlin, and that letters between them have not been accessible to the public up to now – or only to a limited extent – explains why Charlotte hardly features in any biography of Varnhagen. She has simply not been visible.

In the spring of 2020, Charles Harvey and I agreed a price that was acceptable for him and for the library for the 133 letters from Charlotte to Varnhagen in his possession. For Peter Sprengel, this half of the correspondence forms an invaluable source for his book about Varnhagen and his beloved Charlotte. The analysis of this important new acquisition and the publication of an edition with at least one portion of these letters between Varnhagen and Charlotte will rewrite a long chapter in his biography.

Everardus Overgaauw is head of the manuscript department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. This text first appeared in Bibliotheksmagazin 2/21 (p. 50–57).