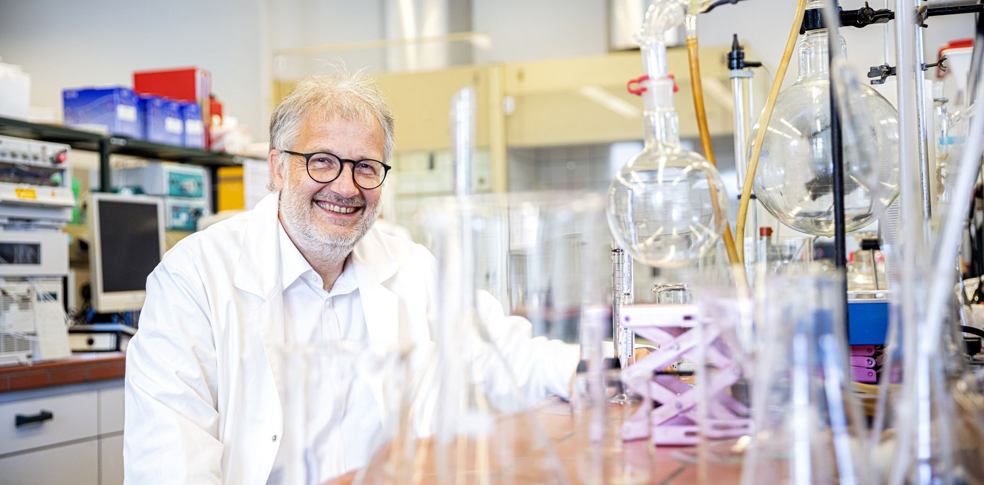

Stefan Simon, the director of the Rathgen-Forschungslabor, on invisible communities in Berlin’s museums, bacteria in New York’s subway, and a fascinating, interdisciplinary project

Professor Simon, “microbiome” has become a buzzword for anyone interested in health and the yoghourts in the supermarket. What is it exactly?

The human body is colonized by a multitude of microorganisms, bacteria, and germs. Many of them live in the intestines, hence the connection with yogurt and nutrition. But we also have an especially large number of microorganisms in the mouth and on the hands. They form the link between the molecular processes in our body and our environment. About half of the cells in the human body are not human cells. This microbiome lives in close partnership with our body – what we call “symbiosis” – and it performs important tasks: for example, it directs our immune system and protects us from diseases.

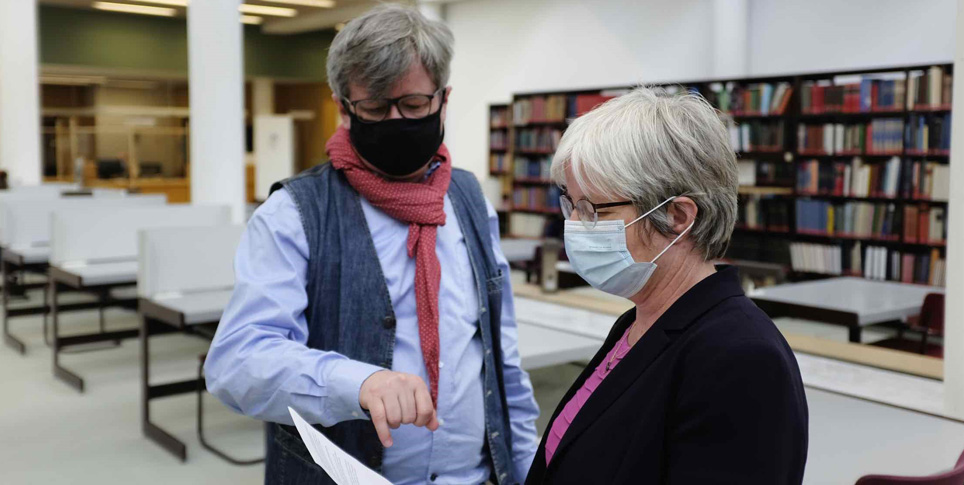

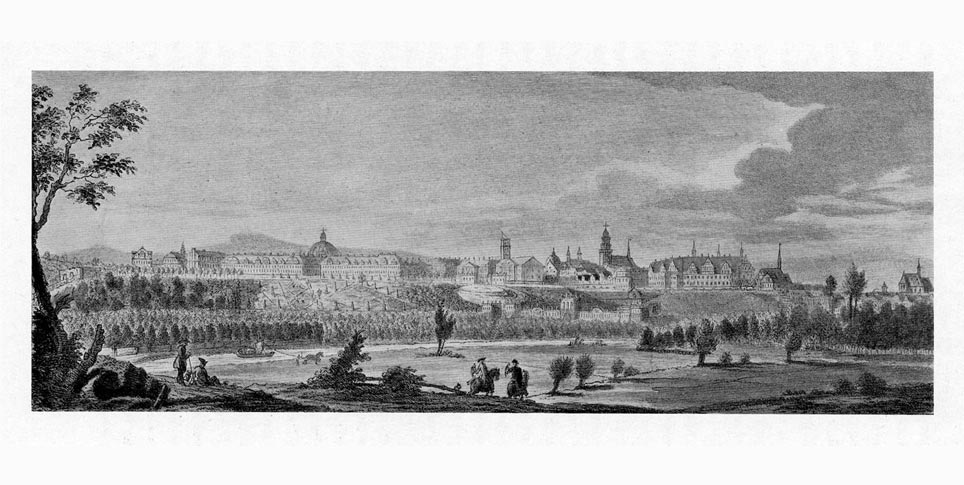

The Rathgen-Forschungslabor (Rathgen Research Laboratory) is considered to be the oldest museum laboratory in the world. You work closely with the collections and institutes of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin). Why are you interested in the microbiome?

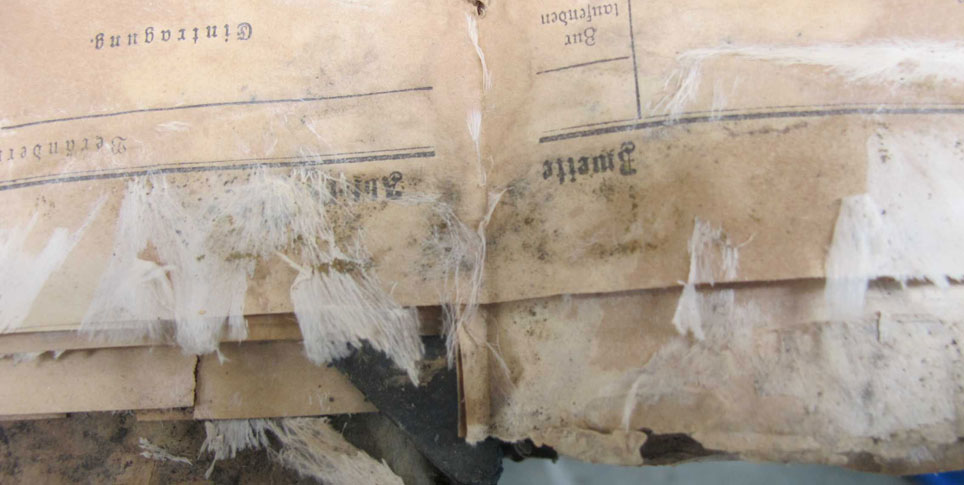

Because microorganisms also live on the works of art, objects, and exhibits in our collections – and we want to decipher their secrets. What information might these microorganisms yield to us? We want to analyze the enormous variety of microorganisms present and to discover new connections between the microorganisms and the objects. That would be absolutely fascinating and it could be the key to gaining entirely new insights. We have no idea yet what we will find, nor have we taken any samples. Microbiome research is a new branch of research, but it is developing rapidly. I am convinced that museums, too, can gain a lot from it. I came to realize that during my work at Yale University.

What makes you so confident?

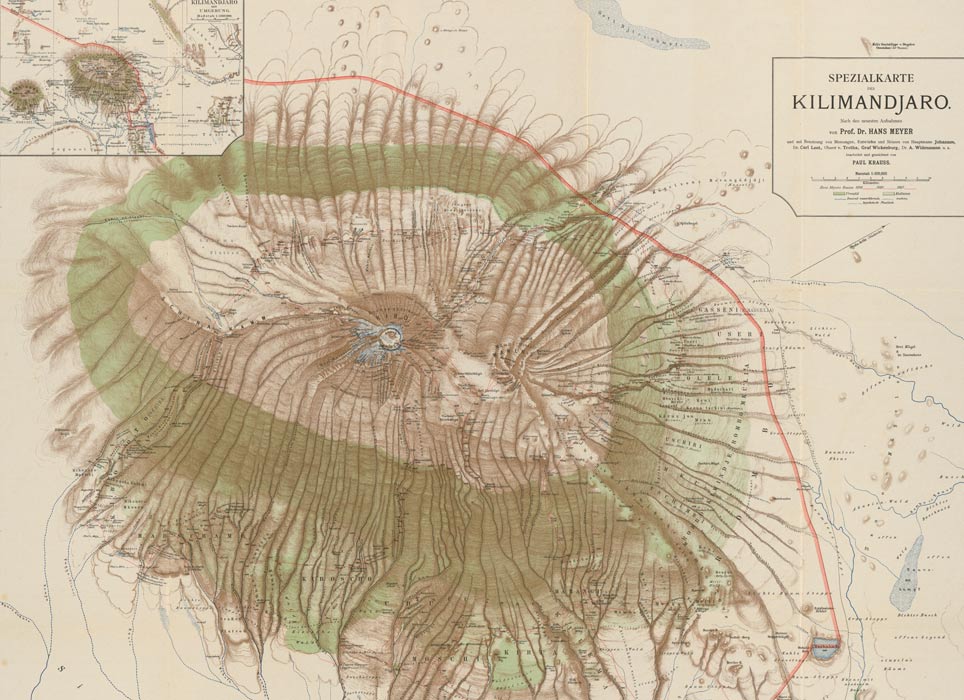

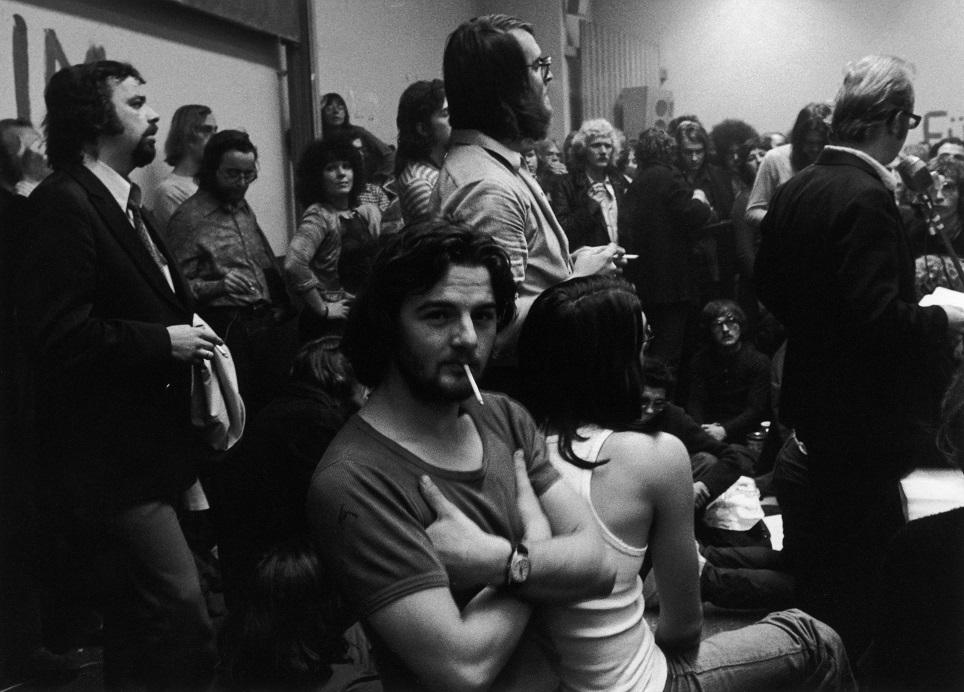

Just look at the famous study that was carried out on the New York subway a few years ago. It ran for many months, with scientists using nylon swabs to take samples from handrails, handles, seats, and garbage cans. Then they compiled a microbiome atlas of the entire city. The results are really breathtaking. The team at Weill Cornell Medical School discovered a balanced, microbiotic ecosystem. It found, for example, that most of the bacteria on the New York subway are completely harmless and that contact with them doesn’t make you sick – perhaps quite the contrary. That should reassure those who are afraid of touching the handles of the Berlin metro trains – at least once the corona pandemic is over. The demographic results of the study are also fascinating: microorganisms that live in the subway stations of Chinatown are completely different from those in Brooklyn, for example, because the composition of the population there is different. Microorganisms thus reveal where people come from.

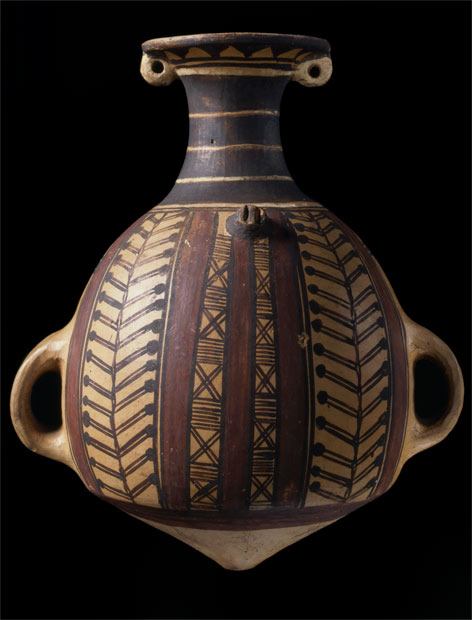

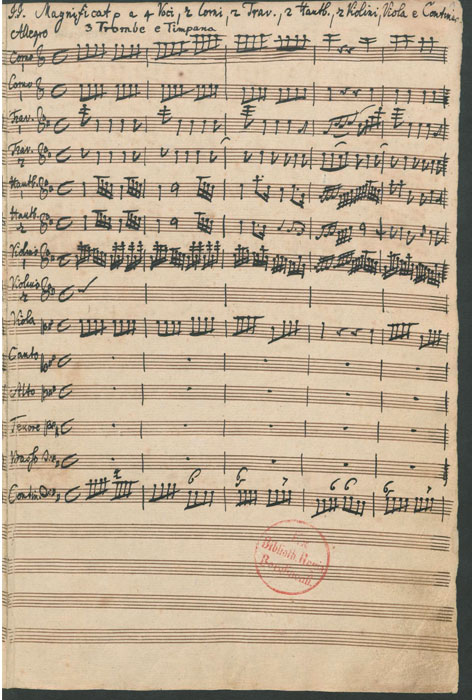

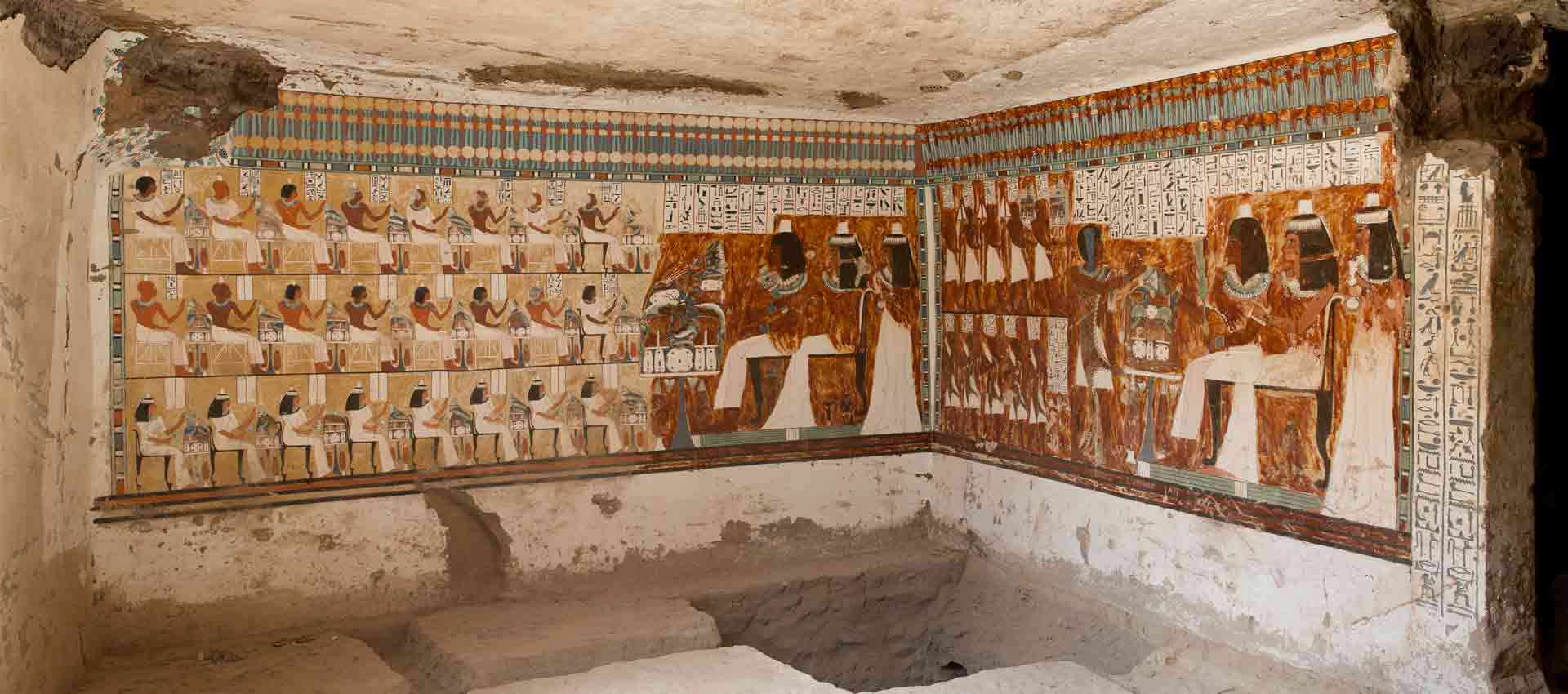

So are you now hoping to find traces of the ancient Greeks on the Pergamon Altar and the bacterial fingerprints of Caravaggio and Velasquez on the paintings in the Gemäldegalerie (Old Master Paintings)?

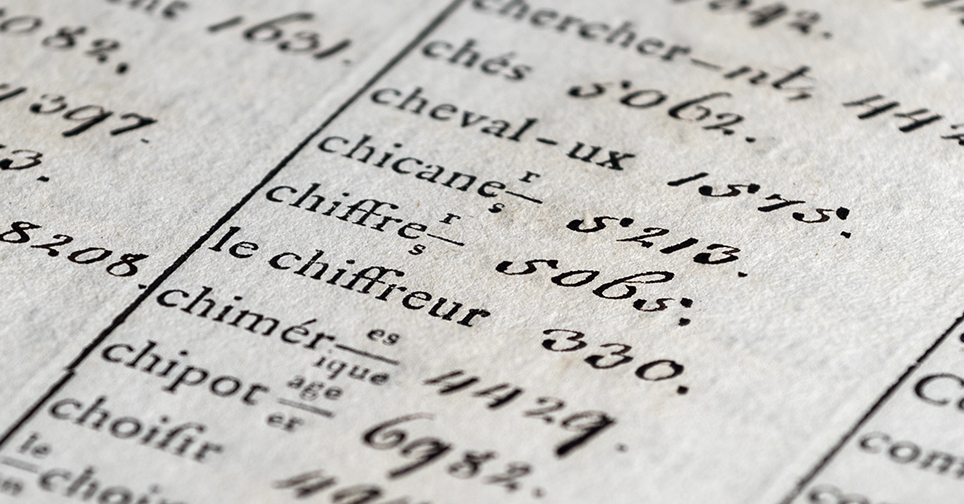

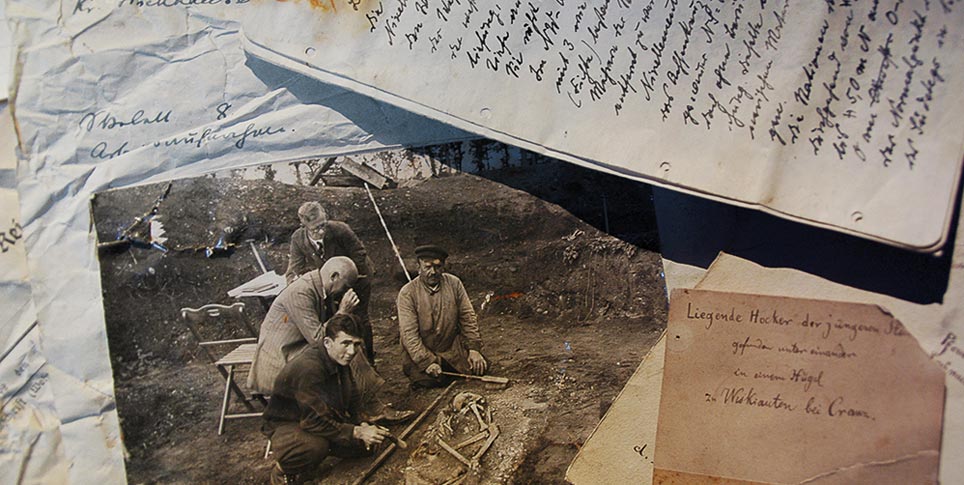

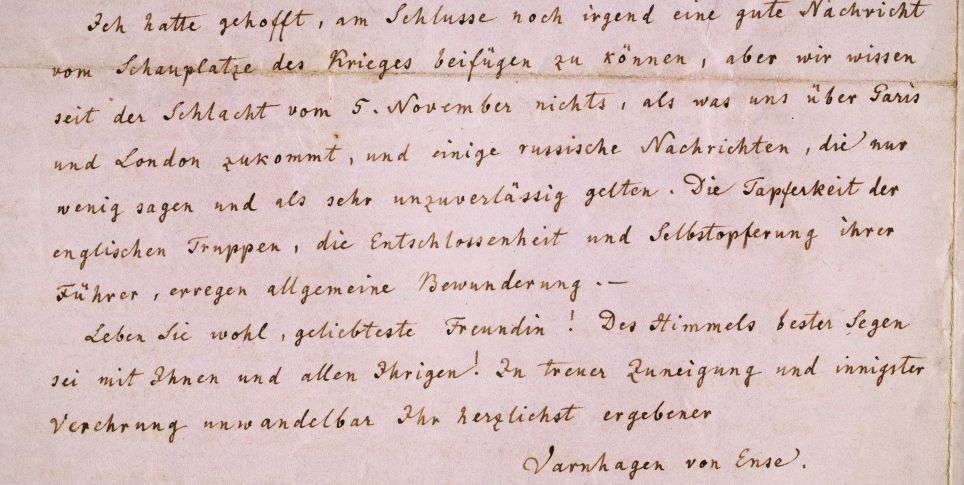

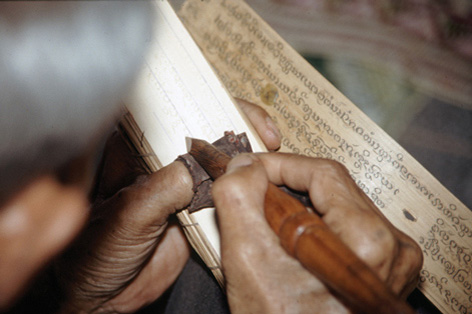

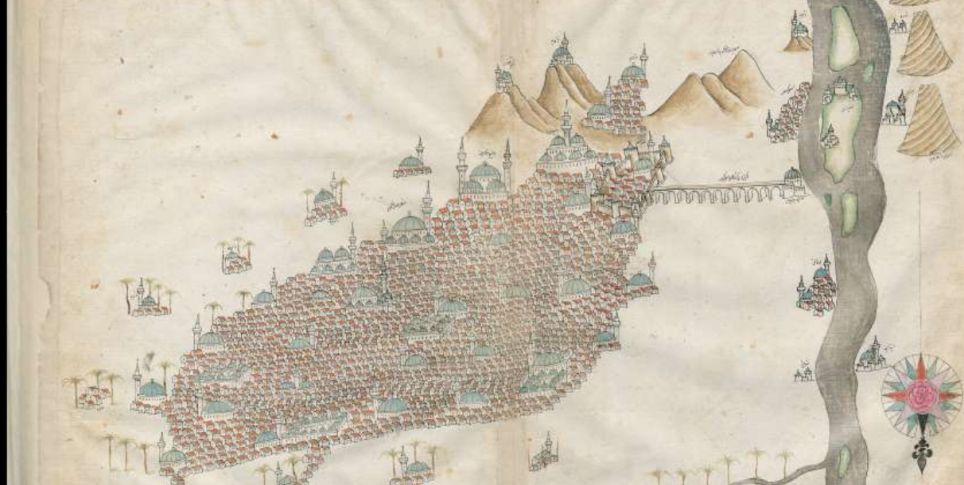

Well, we haven’t got that far yet, by a long way. We’re really still at the very beginning of our research. We’ve opened a new window onto the world and we’re asking questions that nobody has asked before. We want to see whether we can find any microbiotic indications of the environments in which a particular cultural object was created, or stored at later dates. What paths has it taken in all this time? Whose hands did it pass through before it came to us? And of course, we want to know whether the artist, or a collector, has left traces that can still be detected in the exhibitions today. Can we find the artist’s microbiotic fingerprint? But that’s still a long way off. With the help of the microbiome, we initially hope to gain a new scientific tool for establishing the provenance and authenticity of an object. First, we just want to ascertain exactly what there is on the objects’ surfaces – in the exhibitions as well as in the depot. There might simply be traces of people who have only recently come into contact with them, of visitors who have passed by them, or of scientific staff.

The Rathgen-Forschungslabor

As the scientific arm of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, the Rathgen-Forschungslabor (Rathgen Research Laboratory) provides support and advice on issues related to conservation, art technology and archaeometry. It offers its services not only to the museums in Berlin but also to institutions and organisations across the globe. The laboratory investigates museum objects and materials of all kinds, and conducts research on the preservation of historical monuments and archaeological sites.

Just recently, the Rathgen-Forschungslabor was part of the team that solved the Schloss Friedenstein case in Gotha – the biggest art theft in the history of the GDR. You managed to confirm the authenticity of the paintings that had resurfaced. Would that have been any easier with a microbiome analysis?

No, that time it wasn’t necessary. But of course, we do want to make it easier to distinguish forgeries from originals – for example, by detecting microbes from forgers on counterfeit objects – or to show that an object really comes from southern France, say, and not from Thailand as claimed. For museum visitors and the general public, it is becoming ever more important to know who the true owners of the objects in our collections are and how these objects came to be in Berlin.

This applies to the archaeological museums and art collections – and even to the natural history collections if you consider, for example, the dinosaur bones from Tendaguru in the Museum für Naturkunde (Museum of Natural History). That’s why I am delighted that the Rathgen-Forschungslabor and the Museum für Naturkunde are now starting a research project, with financial support from the Richard Lounsbery Foundation in New York. Its title is “Artists and Researchers IN the Collection.” This pioneering work involves other partners too: the Leibniz Institute DSMZ (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures) in Braunschweig, which is doing the microbiological analysis, and the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, which is helping us to evaluate the large amount of data generated.

That is really interdisciplinary.

And how! It still isn’t something that we take for granted. We need data science in order to discover new relationships between molecular patterns and the objects in our museums – and to understand them better. And, of course, we need biology. In return, I hope that our project will help to improve scientists’ understanding of the microorganisms, by explaining how they react to certain objects or surfaces, and how they change over time. In fact, we still know fairly little about these invisible communities. How exactly do they function? I believe this research will make one thing in particular clear to us: even in a museum, we humans are not alone. There are billions of bacteria keeping us company.