With the 4A Lab research program, climate change is coming to museums – and the SPK is just getting really interesting for international scholars.

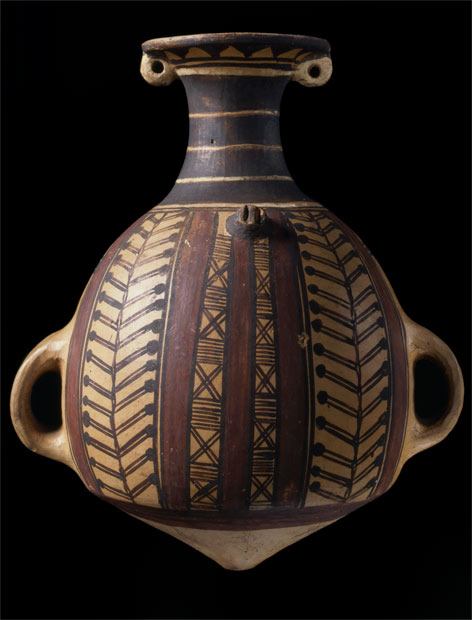

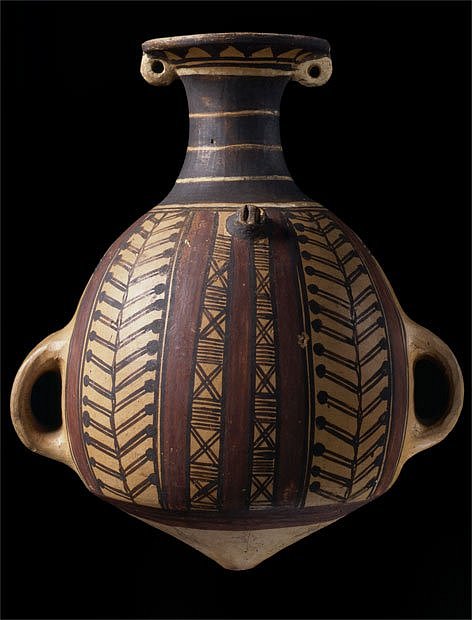

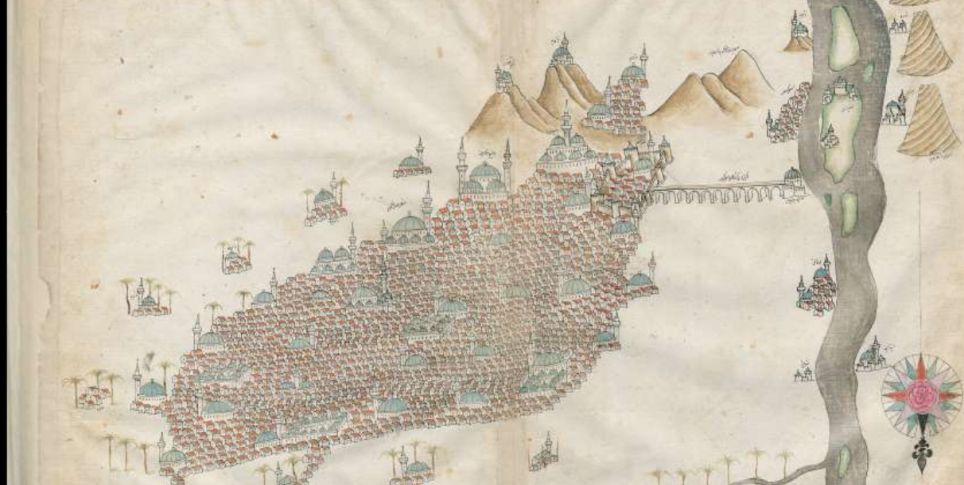

Corn, tomatoes, and cereals: when Bat-ami Artzi browses through the vast depots of the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum), she is looking for plants – or, to be more precise, images of plants with which the Inca and Chimu, the major Andean cultures, decorated vessels such as vases, jugs, and bowls. With thousands of specimens like these in storage at the Ethnological Museum, it is a real treasure trove for the young Israeli art historian. “There is no written evidence from the time of the Inca and the Chimu, so pictures of plants help us to understand the lives of these peoples,” she says. Bat-ami Artzi has many questions: How were the vessels used back then? For particular rituals? At work? What messages do they have for us? And what was the actual significance of corn? How was it bred and grown? And what does that reveal about the people of the time, their living conditions, and the fabric of their society?

When you listen to Bat-ami Artzi, you soon realize that her research is not limited to art history, but touches on other disciplines: archaeology, of course, and anthropology, as much as aesthetics and botany. And if she wants to know whether this or that vessel was customarily used by women or by men, and why and how, then she becomes a gender researcher too. Different disciplines of science strike up dialogues in her work; the rigid boundaries between the subjects dissolve, allowing something new to emerge, new knowledge.

This was a good reason for Bat-ami Artzi to be chosen for the 4A Lab fellowship program, a research project that brings outstanding young scholars to Germany, mainly to Berlin, for periods ranging from nine months to two years. The four “A”s of its name stand for “Art Histories, Archaeologies, Anthropologies, and Aesthetics.” The coordination office for international researchers is located at Villa Parey, a house in Berlin’s Tiergarten. The 4A Lab is a joint project by major cultural organizations: the long-established Kunsthistorisches Institut (Art History Institute) in Florence and the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation) with all of its five institutions, as well as the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and the Forum Transregionale Studien. The aim is to create what the initiators of the 4A Lab call a “space for experimental dialogue.”

Each of the partners contributes its particular expertise. The Kunsthistorisches Institut (KHI), for example, is known for world-class research. Founded in the nineteenth century so that German art historians could undertake research in the Renaissance city, it has now been under the auspices of the Max Planck Society for almost two decades. It has an innovative outlook with a focus on transcultural research in art history. “It is important to us that art history is not viewed solely from a European perspective. We want to examine the aesthetic and cultural phenomena of the subject and its related disciplines from different directions,” says Hannah Baader, who has been researching at the KHI for many years and is responsible for the 4A Lab. She bears the main responsibility for providing the young scholars with mentoring and assistance, be it at the Botanical Garden in Berlin’s leafy Dahlem district, or at the Frankfurter Kunstverein (Frankfurt Art Association) near the banks of the River Main. She plans to organize workshops and seminars with the fellows and create platforms. “We share our knowledge,” she says.

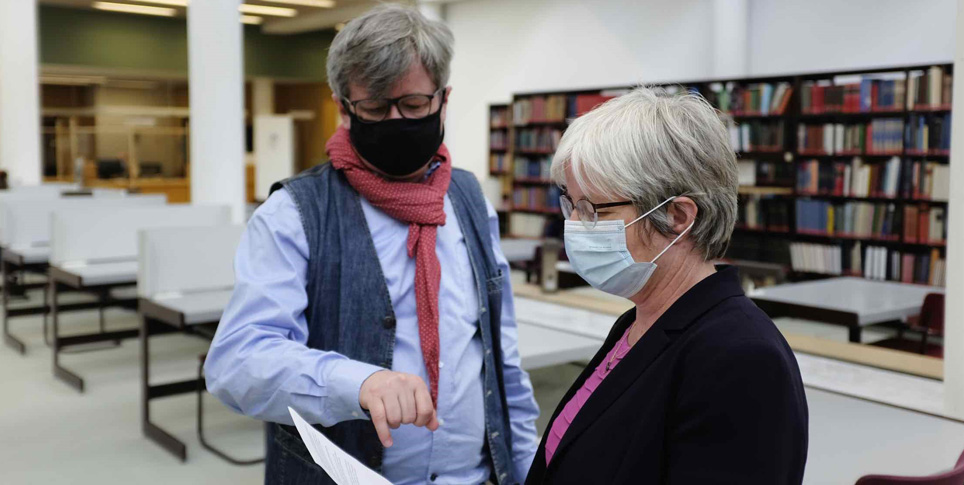

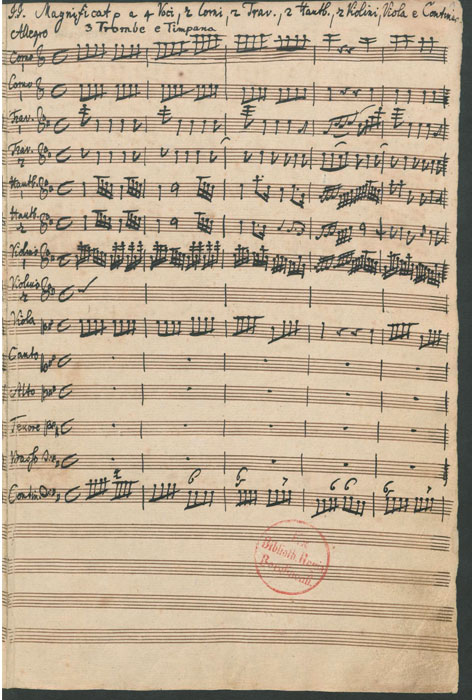

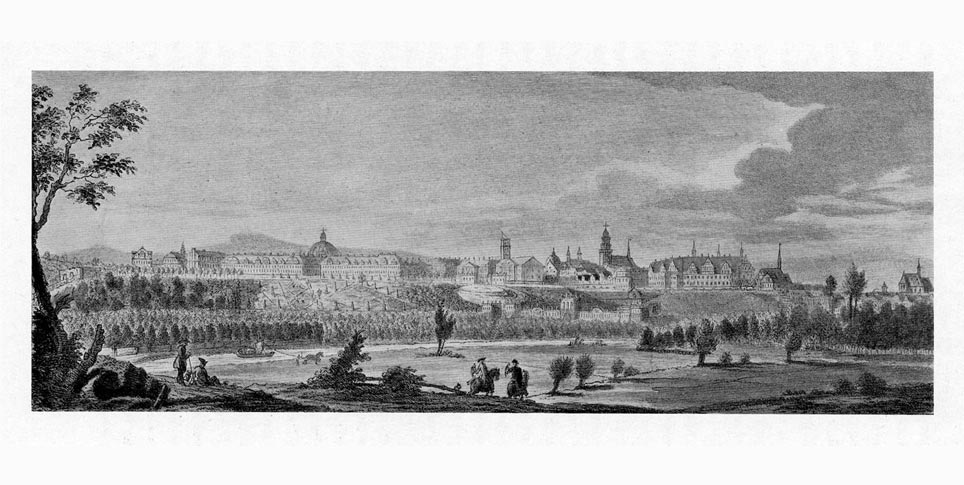

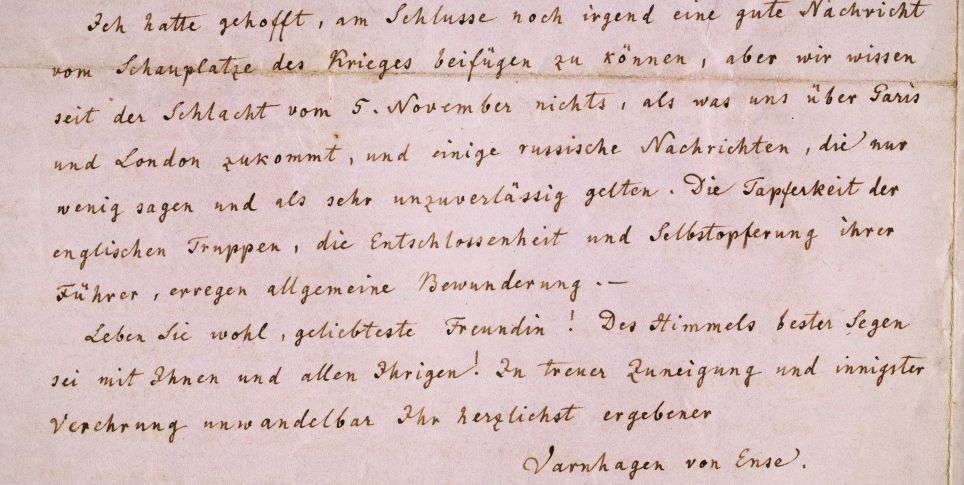

The other major partner in the new research and fellowship network is the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, comprising the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) and four research institutions. Their representatives recently met to welcome this year’s group of young researchers to the 4A Lab and expressed their enthusiasm about future of this collaboration. “With this program, we are attaining new dimensions: we are getting even bigger, even broader, even more international,” remarked Hermann Parzinger, the President of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, at the meeting, which was held in the rooms of Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung (State Institute for Music Research). The program, he continued, offers a “great opportunity” to bind talented young scholars to the SPK and to generate new knowledge from the Berlin collections. With the 4A Lab, the SPK is enhancing its already strong international profile. After all, Berlin with its collections, archives, libraries, and universities offers a unique research infrastructure that is extremely attractive to scholars internationally. Nevertheless, Parzinger attached particular importance to the aspect of reciprocity: “We don’t just want to be hosts, we also want to learn from you.”

Denn „4A Lab“ hat Modellcharakter. Indem es die Grenzen nicht nur der Regionen, sondern vor allem der Disziplinen und schließlich sogar der Organisationen und Einrichtungen überschreitet, geht es neue Wege. Dazu gehört sein Anspruch, auch gesellschaftlich relevant zu sein. Denn zum Thema hat es in diesem und nächsten Jahr „Pflanzen“, verbunden mit ökologischen Fragen – und trifft damit den Kern der Zeit. Angelehnt an die „environmental humanities“ entstehen neue, eigene Zugänge zum Klimawandel, entstehen neue Erzählungen zu Umwelt und Umweltschutz: Ohne Pflanzen können wir unseren Lebensraum nicht bewahren. Pflanzen geben uns Nahrung und bieten Erholung, sie verlangsamen die Erderwärmung – und sind Teil der Geschichte des Anthropozäns, jener Epoche, in der der Mensch die Natur endgültig seiner Macht unterworfen hat. In einer Zeit, in der sich Museen und Archive auch in Berlin in einem Prozess des Umbruchs befinden, sich öffnen und sich stärker für ihr Publikum interessieren, lädt „4A Lab“ ein zur aktuellen Debatte. Kurzum: Das Projekt macht Museen und Archive zu Orten des gesellschaftlichen Dialogs.

Link for Additional Information

4A Laboratory: Art Histories, Archaeologies, Anthropologies, Aesthetics

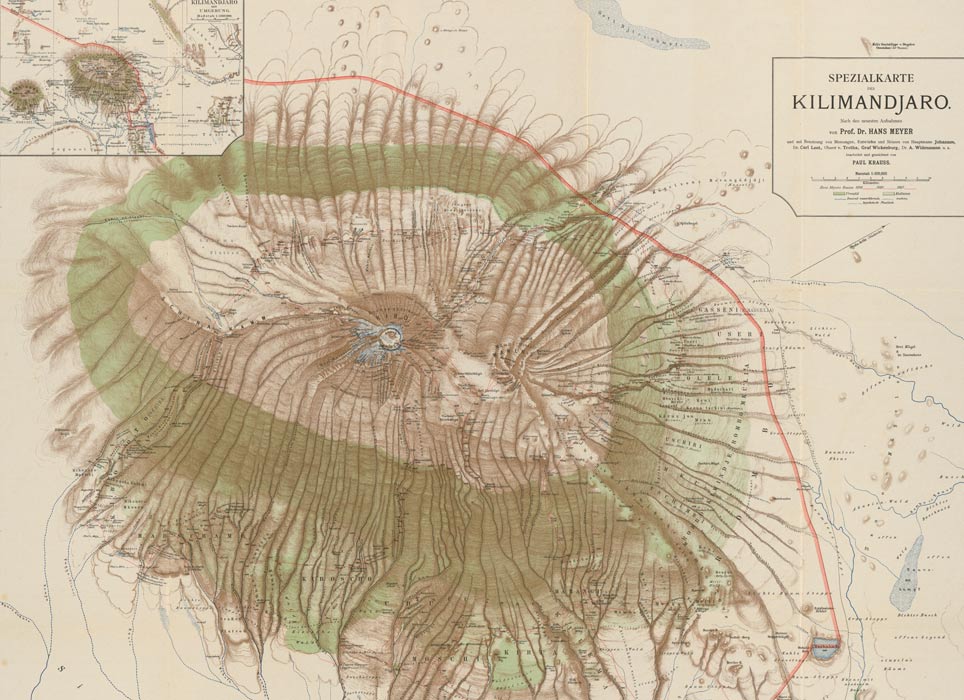

That is because the 4A Lab is conceived as a model project. It breaks new ground by transcending the boundaries not only of geographical regions, but even more so of the academic disciplines and ultimately of organizations and institutions. In doing so, it also aims to be socially relevant. For instance, the theme of research this year and next is “plants” and related ecological questions, which goes right to the heart of today’s concerns. The environmental humanities form a basis for the emergence of new, independent perspectives on climate change as well as new narratives about the environment and environmental protection: we cannot safeguard our habitat without plants. Plants are a source of nourishment as well as physical and mental recuperation; they act as a brake on global warming and they play many parts in the history of the Anthropocene – the era in which mankind finally subjugated nature. At a time in which museums and archives in Berlin are undergoing a process of radical change, opening up and reaching out to broader sections of the public, the 4A Lab invites people to join the debate. In short, the project is transforming museums and archives into places for social dialogue.

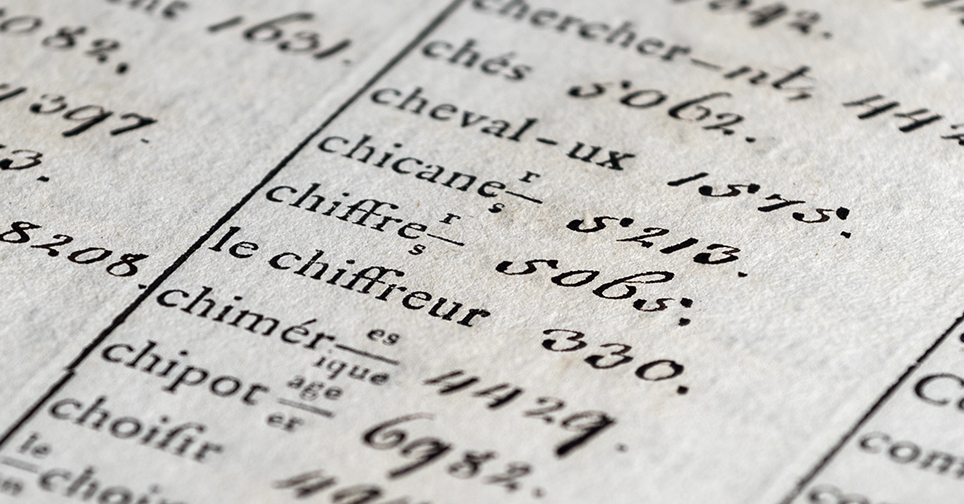

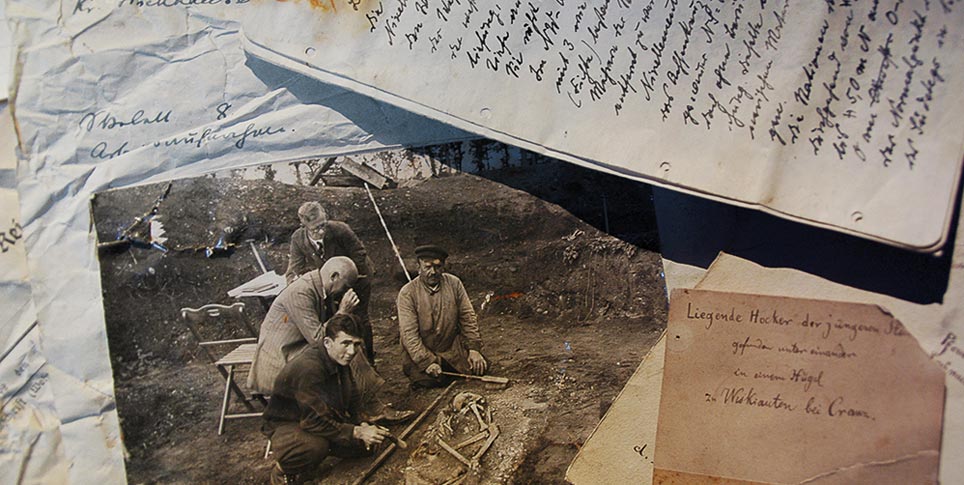

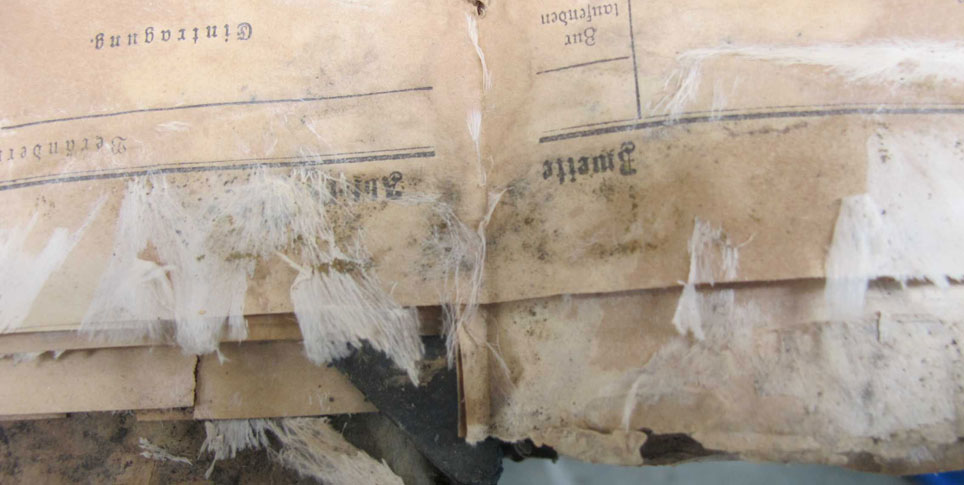

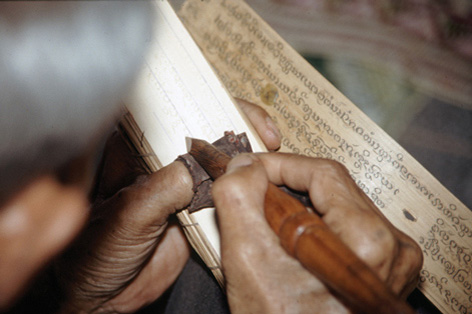

As in our culture, plants have always been present in our museums and archives. After all, the canvases of the paintings are made of linen, while the Bladelin Altarpiece, painted by the Dutch painter Rogier van der Weyden around 1450, consists largely of wood. And what about the mushrooms? Lucas Vanhevel, one of the recipients of a 4A Lab fellowship, discovered them on the roof of the stable, near the top of the picture, when he was studying works in the Gemäldegalerie (Old Master Paintings Collection). Why are there mushrooms in a depiction of the birth of Christ? “Because mushrooms have signified the concept of spontaneous generation for many centuries,” explains Vanhevel, a specialist in the cultural and historical aspects of these organisms. For him, as an art historian, they raise a number of interesting questions: Since when have we known that fungi and plants are merely related? Why do many people find them uncanny, even mystical? And what role did painters once play in generating scientific knowledge? Vanhevel enthuses over the huge amount of research material stored in the Berlin archives: the botanical manuals, the engravings, and the drawings. It seems that wherever he looks, he finds mushrooms – edible mushrooms, toadstools, psychedelic mushrooms...

The 4A Lab, too, is expanding our consciousness. Its revelation, you could say, is that plants are present throughout Berlin’s depots, archives, and exhibition halls – a web of life underlying them all. Offering access to young scholars with fresh eyes and an outside perspective is making it possible to unlock new interpretations of the collections and call long-established assumptions into question, especially the structural ones. Or, as Barbara Göbel, the Director of the Ibero-American Institute, put it when meeting the new fellows: “It is your job to disturb us Berliners!”