Provenance researchers can use the German Sales data base to dive deep into art stories from 1901-1945.

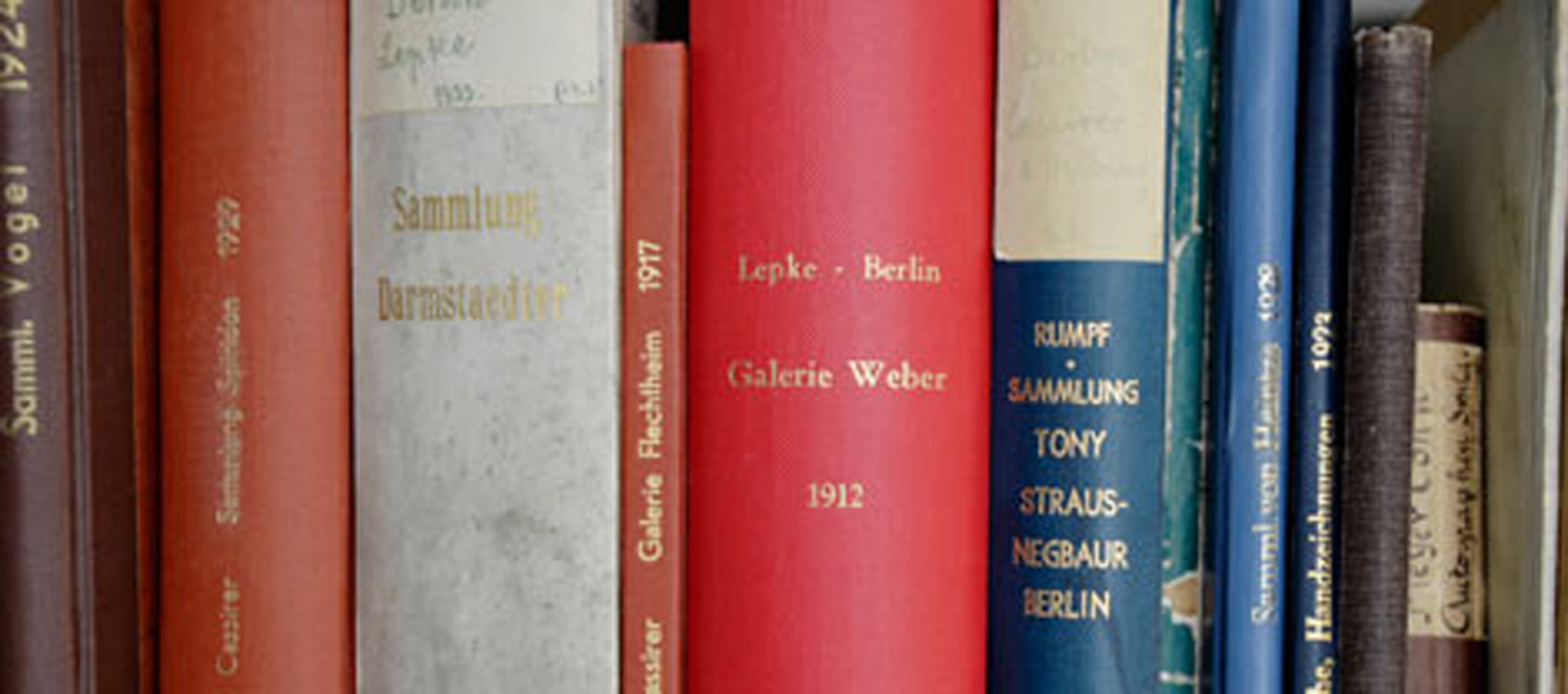

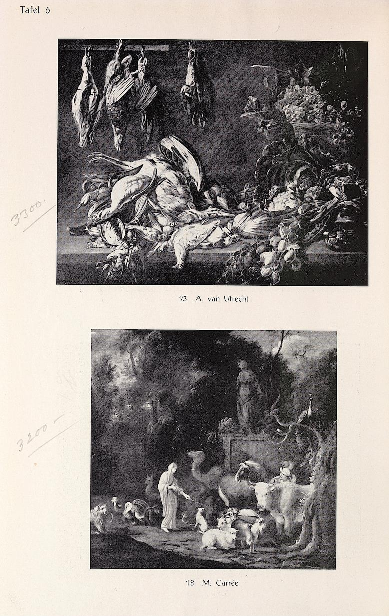

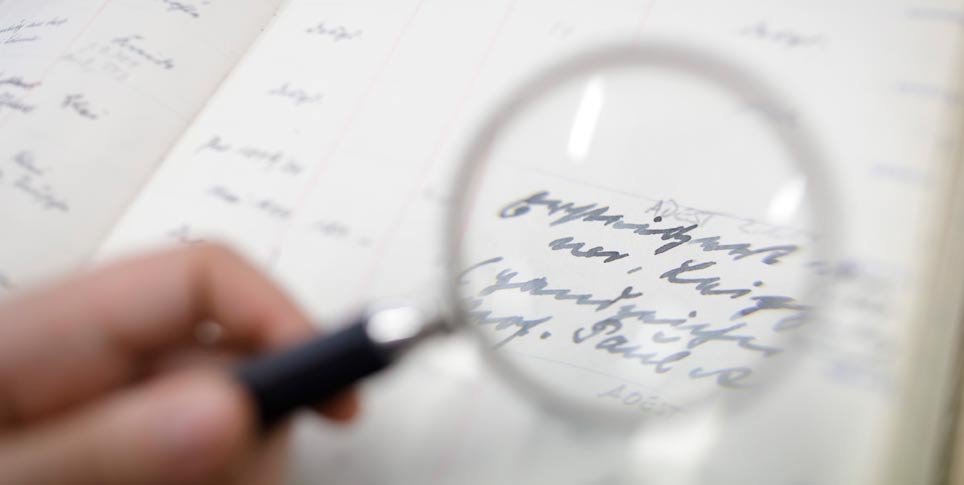

When a work of art is 500 years old, it has surely had more than one owner during its history. The works often passed through ten or twenty pairs of hands in the course of time, usually via auction houses that would broker the sales. Files, inventories, and especially auction house catalogs play a large role in the work of provenance researchers, who reconstruct the stories of works of art today. They provide the researchers with clues as to ownership, and when and how the object changed hands. “Auction catalogs are written indications of change of ownership and therefore, an important source for provenance research,” explained Joachim Brand, assistant director of the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library). “But such catalogs are not being collected systematically. They are available. of course, in museums or museum libraries where collection curators use them in their daily work. But there is no institution that has always collected all auction catalogs.”

Britta Bommert und Joachim Brand ©Katrin Käding

German Sales is a pioneering project that connects the Kunstbibliothek of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin), Heidelberg university library, and the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles and now largely fills the gap in this service for the German-speaking regions. Around 9,000 catalogs, which were published between 1901 and 1945, have been completely recorded, digitized, and indexed in two projects that were supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation, DFG). Subproject 1 covered the years 1930-1945 and Subproject 2 the catalogs from the years 1901-1929. The catalogs come from more than 390 auction houses in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. These sources, which are indispensable for provenance and art market research, are now available with open access for the first time. A total of 650,000 pages can now be researched in full texts across catalogs. German Sales was made part of the Provenance Index, a Getty Research Institute data base, which already contains comprehensive data on the historical art market in Great Britain and Italy.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the German-language auction market with centers in Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich, Vienna, and Zurich was one of the world’s most expansive hubs for art. The auctioning of numerous private collections, the activities of museum directors and curators in the art trade, the Great Depression, and the confiscation and expropriation of art by the Nazi government mark its equally varied and complex history. German Sales makes it possible to identify and reconstruct the object biographies, actors, and places involved in unheard-of clarity. The bibliography of Subproject 2, which has just been completed, contains registers linked to the auctioned collections, the auction houses, and the writers of the introductions along with a list of all catalogs. These include major art historians like Wilhelm von Bode, Max J. Friedländer, Julius Meier-Graefe, and Otto von Falke, making new information on the auction market and its protagonists available.

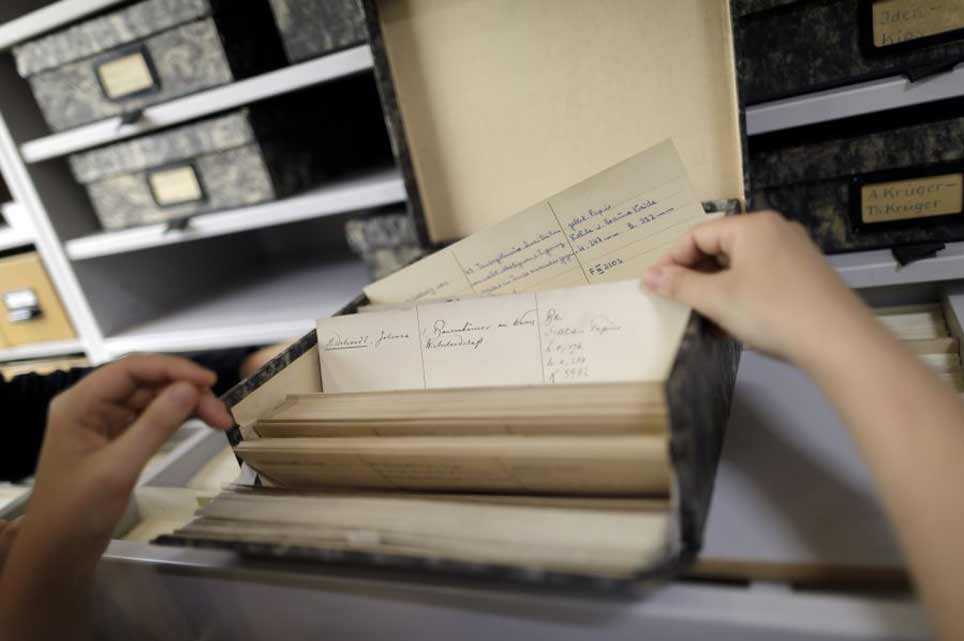

This new service makes work much easier for provenance researchers, whose work serves to expose acts of injustice committed by the Nazi dictatorship, among other things. Britta Bommert, a scientist who supervised the project in the Kunstbibliothek together with project director Joachim Brand, has received lots of positive feedback. “It is true that provenance researchers are very happy about this project since finding all of these catalogs, going to the libraries, and searching the collections takes a lot of work,” she said. “That is one of the main reasons that provenance research involves so much travel: there was no central access point to the catalogs. I think that we have made a major contribution to speeding up and reducing the costs of provenance research.”

Before German Sales was published in the Provenance Index, researchers had to send an individual inquiry to each library and institution that had catalogs and travel there to conduct their research. All of this information is now compiled online and easy to view. “To find all the catalogs that were published in German between 1901 and 1945, we started with the extensive collections in the Kunstbibliothek of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and the Heidelberg university library,” recalled Bommert. “After that, we contacted other large libraries and museums with long histories and asked for their help.”

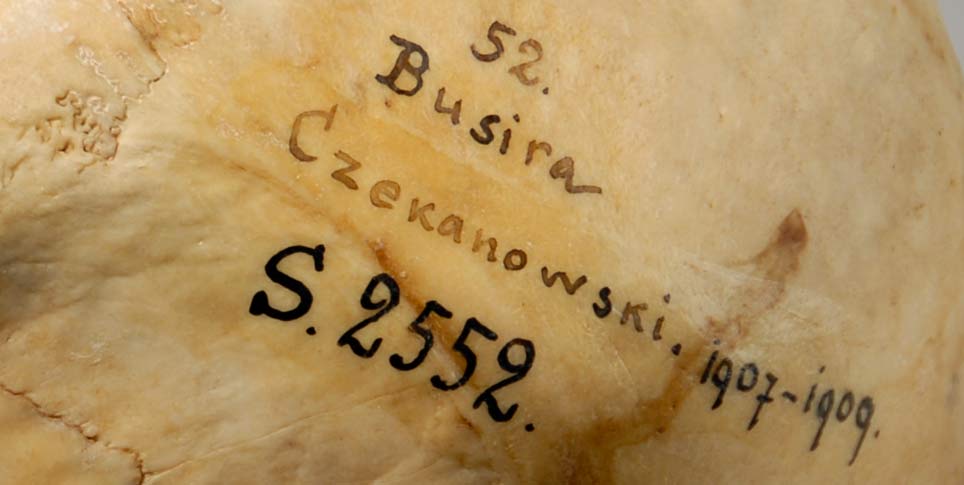

Now that the project is completed, the broad range of source material presents an overview of brand new knowledge about the art market from 1901 to 1945. It has only become possible to quantify the number of active auction houses during that period through the project. Now the history of the individual businesses can be reconstructed in greater detail and the individual auction houses can be characterized more exactly. “We can also acquire other data. For example, we can find out when an especially large number of auctions took place and which types of art they featured,” said Bommert. The possibilities will not only move research on Nazi confiscated art forward but also bring exciting new information on the trade in ethnological objects in the early 20th century to light. Joachim Brand can also imagine expanding the database: “It would be nice to get closer to the present. We could also go further into the past, into the 1870s or earlier…”

In any case, the potential of German Sales will keep researchers busy in the near future and we can expect to find exciting stories hiding in the immense treasury of sources.